“I grew up not always feeling comfortable with the fact that I was Vietnamese. But it's not unique to being Vietnamese, right? It’s just unique to being not in the majority.”

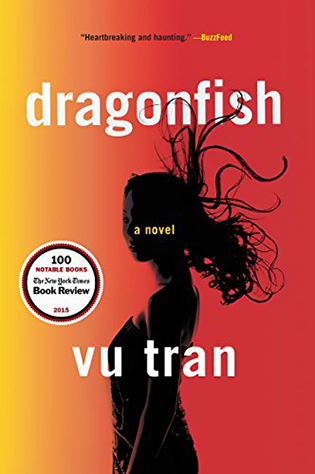

Ever since he was in the first grade, Vu Tran knew he wanted to be a writer. Now, he is the author of Dragonfish, a book about an Oakland police officer, Robert, who is on the search for his ex-wife, Suzy. He is also an Associate Professor of Practice in English and Creative Writing at the University of Chicago.

In this interview, Tran insightfully talks about growing up in Oklahoma, the Americanized view of Vietnam, writing about your community as a minority, and more!

What influence did growing up in Oklahoma have on your writing?

I think it’s influenced me in countless ways that I’m still kind of becoming aware of and realizing. I grew up in a predominately white community. North Tulsa was predominately African American, but the rest of Tulsa and the suburb of Broken Arrow, where I technically grew up, was very white.

There was a small Vietnamese community in East Tulsa, but we grew up in South Tulsa, so my parents wanted us to stay away from that. It was a strange decision, they had their reasons, but I had a happy childhood. But I always felt, unsurprisingly, on the outside of things. And what's interesting about that is when you’re on the outside, you want to get in on the inside. And when you want to get on the inside, you’re much more sensitive to what the inside looks like. You become much more detail-oriented and more critical-minded about what the majority, or the inside, is like, and I think I was always frustrated growing up in that sense. But now that I think about it, I realize that it was a really good place for me to be because, especially as a writer or as an artist, when you’re on the inside, your kind of like “Okay, I’m fine.” You don’t feel a need to look around and be thoughtful about your environment as much, I mean depending on the person, obviously. I was always very, very keenly interested in my environment and what it was like because I wanted to be like everyone, but I think that’s been good for me. I think that would be one of the biggest effects growing up that way had on me.

Explore Writing and Literature at Coastline

I read in an interview that you said what sets apart the Vietnamese experience in America is the idea of Vietnam in American culture. Growing up, how do you feel you were impacted by the Americanized view of Vietnam?

The United States tends to create a narrative whether it’s the USSR, the Soviet Union, or right now it’s China and Russia. It’s not that these ideas are entirely lies, but there was always this sense that - because in the Vietnam War, the communists, and the Vietnamese communists, were the enemy - you grow up with that idea of Vietnam not really being a country or a culture but being a war, and with all the connotations that bring to a people. And of course, you see that in movies, in all the Vietnam War movies, and even Vietnam War fiction. That idea of Vietnamese people being peasants and kind of sub-human in that way.

So, you grow up in that kind of cultural conditioning. It affects your pride in your own heritage, and I’d be lying if I said there wasn’t some shame that came with it. It affects how you define who you are. It’s a complicated thing. I grew up not always feeling comfortable with the fact that I was Vietnamese. But it's not unique to being Vietnamese, right? It’s just unique to being not in the majority.

In Dragonfish, the main character is a white police officer, and the ‘bad guys’ are the Vietnamese characters. I feel like as a minority, there is a lot of pressure if you're a writer to present your community in a certain way to others. So how would you advise minorities to work through that worry of not presenting your community in the most perfect way?

I wrote the novel the way I did because the idea for Robert was that he was a kind of white savior character, and I was interested in writing a white savior character - that kind of heroic figure that enters an alien culture and somehow becomes part of the people and can save the people. I wanted to see what it would be like when he can’t be the hero or the Savior he wants to be, what does he become? I was not necessarily trying to make him into a negative figure by any means, but I was interested in ‘What do you do when you can’t play the role that you want to play?’ Whether it was in that situation, the thriller plot, or whether it was in his marriage to this woman who was very unlike him, at least her background is very unlike him.

But the other thing is that Robert is also an outsider and there’s a lot of me in that character. That sense of not being able to access a person - in this case, it was his wife that he loved - or it’s an inability to access a community, which is the community of Vietnamese characters there. Your question is such a good one, I mean how do you write about your own community? You think about ‘what is bad?’ and how should you portray them––in a negative light or positive light?

Frankly, I don’t think in terms of good or bad or negative or positive, I think in terms of our complex humanity. We all have reasons for doing what we do, and everyone is complex in that way. I prefer to look at that aspect of their character. I mean obviously, the novel is dealing with systems of morality, and how they can be distinguished from culture to culture as well. But also, I was trying to use the tropes of crime fiction, of the idea of who’s supposed to be playing the good role, and who’s supposed to be playing the bad role. And I wanted to complicate those roles.

I read that one of the features of noir fiction is a bleak outlook on human nature. What did you set out to say about human nature with Dragonfish?

As a ‘civilized society,’ we are kind of presenting our most straightforward, easy-to-digest versions of ourselves. That’s how we get along. Everyone agrees to the same kinds of morals and social codes and that’s how we pretend to get along - and we do get along. Civilized society requires that kind of performance of legibility, but our true nature is much more irrational, much more complicated, and much more ambiguous. And so, genres like Gothic black horror fiction and crime in our fiction bring that to the surface. And I think the best versions of that don’t necessarily resolve it because it's irresolvable. And it's bleak in that way because it’s a confrontation with the notion of mortality, the fact that we’ll all die.

I don’t mean to be depressing, but it's just the reality of things and it's hard to think about those things. There’s no good or bad when it comes to the fact that we all die. Good people die. Bad people die. That’s just a fact of nature. What is interesting is what people do to deal with that reality. Other people deal with it better but then lie to themselves and to others. Crime fiction, because it's this idea of justice, good and bad, cops and robbers, people of law, and criminals, it sets up this binary that’s just not stable. It doesn’t work that well. And so, when it breaks down, it's just bleak.

Was any part of the writing process for Dragonfish cathartic for you?

Yeah, I think it always is. Catharsis is an interesting word because people tend to think of it as a purging of emotions - it’s kind of all at once, or at least that’s how I learned it when I was first reading Greek drama. But my kind of catharsis is just very gradual. Over the course of time, you do feel, especially when you’re writing about tough things, what’s tough for you to confront, it doesn’t feel like a catharsis because you just live in it for three, four years, however long you work on the book, so it sits inside you a lot. But it’s good. I feel like it’s a very productive feeling personally because I feel like I understand myself better. And I understand people and the world a little better - at least I hope it’s a better understanding. And it is cathartic in that sense.

Especially in the idea that you can interrogate the different versions of ourselves that we carry around the world. It’s all us, just these other versions that are slightly different and slightly capable, or incapable of certain things at different times. And it’s kind of frightening to know that you can kind of evolve or change or have that different aspect of yourself. At least I feel that way about myself and about people.

Learn More About NEH Institute @ Coastline

You’re also a professor. How does being a writer influence how you teach, and how does teaching influence who you are as a writer?

Well, it’s a great deal. I have professors who tell me don’t teach if you want to write, that will get in the way of writing as an artist. And I found that especially teaching here at the University of Chicago, it has its flaws this way, but it’s a very conceptually-minded place. But it’s forced me to really conceptualize my work in ways that I think have made me not just intellectually, but emotionally enriched by teaching.

It’s such a great luxury and privilege, too, to work out a lot of my ideas in my classes in the context of also helping my students do that. When I taught a gothic literature class this fall in London, in our study abroad program, I was able to research my work and I was able to help my students understand the history and tradition of gothic literature more. And that has helped me write. It’s made me think about elements of craft in ways that I probably would not have if I didn’t teach.

For example, I’m writing a class on finding and refining your voice, your writer’s voice, and it’s made me really think about things. For example, the fact that I don’t think teachers ever really ask students ‘How do you want the reader to feel?’ It seems beneath us to ask that. To get the reader to really interrogate the same ideas that we’re exploring, you first have to ask, ‘Well what do you want the readers to feel? Do you want them to feel sad? Do you want them to feel in awe? Or do you want them to feel a kind of profundity? Do you want them to be scared?’ These things are so important to the kind of voice that you want to develop in your work. I didn’t think about these things until I taught the class. Teaching has been crucial in my writing.

You knew you wanted to be a writer when you were in the first grade. If you could go back and tell that version of yourself anything, what would it be?

The thing about telling your younger self these things is that your younger self is not going to listen to you. I just think that’s kind of the common reality. I mean, I would tell my younger self to be patient. I’m a very impatient person, and the truth of the matter is everything good that has happened to me took a very long time. Some people develop their voice––or whatever you want to call it––their interests, their thematic concerns, their worldview––some writers develop that really early on, like even in their 20s. I had a style, I had an aesthetic, but I didn’t really understand what I wanted to write and the kind of story that was important to me until right until my late 30s. And I really don’t feel like I truly understood it until now, honestly, and I’m 47.

So, it took me a long time. I failed to publish my first book when I was 30. A book of stories. I wouldn’t write those stories now the way I did then. I’m proud of them in many ways, but I would write them so differently because I have such a different idea now of the world and of the style that is required to write about the world the way I see it now. It just took me a long time to figure that out. I think I always had the talent, to be honest, but I just didn’t have a sense of the world, a sense of myself. And my younger self was just so impatient to be the best writer in the world. I would tell him that, and he would ignore me, and continue being as impatient as I was.

What is one book you think we should be consuming right now?

I have very different tastes here and there, but I would say that the writer that people can learn the most from is Alice Munro. If you could read one of her books I would say Open Secrets, which was a collection that she published in 1994 or 95. I’ve learned so much from her. I don’t necessarily write like her, but in many ways I do. I just think she’s the most innovative, and the wisest writer that I know, that I can think of. I don’t feel like I’ve ever read a sentence in her fiction that feels untrue, that feels performative, morally righteous, or thoughtless.

I would go so far as to say that she has something that only a few writers have that Shakespeare had the most of which is just this deep and broad range of human understanding. There are so many different kinds of characters in her fiction and people don’t necessarily think that because they think she writes about domestic situations in Canada, and young women coming of age, but the range of her characters and her situations, and her plots, and she's so experimental. But it requires a certain I think emotional maturity to read her. I didn’t like her when I first read her when I was 24, 25. I was just not mature enough. But yeah, I would say her.

Vu Tran is one of 36 scholars participating in Coastline’s NEH Higher Education Faculty Institute titled, "Fifty Years Later: The Vietnam War Through the Eyes of Veterans, Vietnamese, and Southeast Asian Refugees". This program is being offered through Coastline to enhance undergraduate teaching and expand upon the intricacies of the Vietnam War. If you want to learn more information on this event, see here.